|

I started this blog expecting to spend at least a couple of years photographing and researching the tools in the Tison Tool Barn. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, I am stopping my work with the Tison Tool Barn for an indefinite period. I hope that I will be able to eventually resume that work, but I do not know when. I just hope that you have enjoyed reading this blog half as much as I have enjoyed writing it.

1 Comment

People are interested in old tools for a variety of reasons. Some like to collect tools. Some like to restore tools. Some like to buy and sell tools. Some like to use old tools to make things. I am interested in the history of tools, how they developed and how they were used when they were new. Most people interested in old tools are motivated by more than one of those reasons, but I am focused mainly on learning more about the history and use of tools. As I have grown older, I have come to realize how sophisticated pre-industrial technology could be. I first began to see that sophistication in the construction and operation of sailing ships. (The appreciation came in part from reading sea novels. I may also have been influenced by the fact that my grandfather was a ship's carpenter when he was a young man.) More recently. as I began researching tools in the Tison Tool Barn, I also came to appreciate the sophistication of coopering (making casks), and building wheels. I recently finished reading The Oregon Trail by Rinker Buck. The book is a memoir of the author's journey in 2011 by mule-drawn covered wagon from Missouri to Oregon. I started the book because I wanted to learn more about the Oregon Trail. It is not a history book, although Buck includes various tidbits about the history of the trail. I am mentioning the book in this blog because Buck also includes some details about the history and construction of wagons. Buck's book has now added wagon-building to my list of pre-industrial technologies.. In the 19th century many of the traditional crafts or technologies were industrialized. Production moved into factories, with power machinery, specialization of tasks, interchangeable parts and, in at least some cases, assembly lines. Ship building was resistant to such changes, but the manufacture of goods such as barrels and other casks, wagons, wheels and hand tools, became largely industrialized in North America and parts of Europe. I find it somewhat ironic that hand tools became cheap, standardized, and widely available at a time when so many traditional crafts were industrialized. I started on this musing about the transition of the production of many products from craft to industry from reading about wagons. The Tison Tool Barn has few items related specifically to wagons. It does have a couple of wagon jacks, donated early this year by Robert Sherman. Wagon jacks, as would be expected from the name, were used to raise a wagon axle enough to remove a wheel, either to replace a broken wheel or to grease the axle. Two types of wagon jacks in the Tison Tool Barn. Photos by Donald Albury. The Tison Tool Barn also has a wheel skid shoe, donated by Robert Sherman, which was used for helping to brake a wagon. Motor vehicles normally have brake systems that will stop and hold them on a down slope. In addition, the engine, if it is engaged through the transmission to the wheels, will help brake the vehicle. Animal-powered vehicles do not have those advantages. The brakes on wagons did not apply enough friction to stop the wagon, except on the most moderate of slopes. Moreover, if the draft animals pulling a wagon feel the wagon pushing against them, they will often panic and try to get out of the way by running away. Wagons therefore had to be restrained when going down hill. In extreme cases, a rope was tied to the rear axle and run around an anchor point at the top of the hill, so that the wagon's descent could be controlled by slowly paying out the rope. Another solution to restraining a wagon was to prevent the rear wheels from turning, creating friction between the wheel tires and the road. One method for achieving this was using skid shoes. A skid shoe was placed under a rear wheel , and held in place by a chain attached to the under side of the wagon bed. This placed the underside of the skid in contact with the ground. Sources:

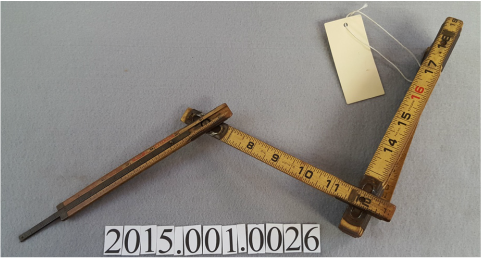

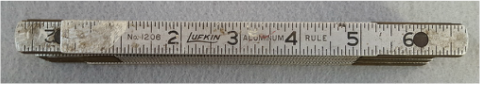

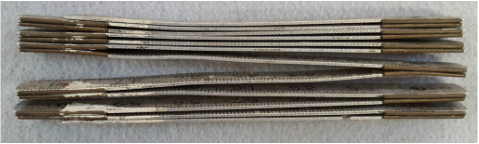

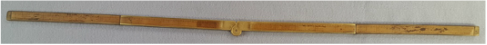

In this post I will look at a type of folding ruler commonly known as zig-zag rulers, and an interlocking or slide ruler. Zig-zag rulers are folding rulers made up of a number of short pieces with locking hinges connecting the pieces. When fully opened, a zig-zag ruler is often six or eight feet long, and is stiff enough to be held in one hand while being used to measure. These are the tools that I have always thought of as "carpenter's folding rules." I bought one when I started my (one and only) summer construction job in 1962, and I have one in my garage today. The first zig-zag folding ruler from the Tison Tool Barn collection is this Lufkin Red End rule with a slide extension. The rule is 96 inches long when fully extended. The model number on this tool is badly smeared and unreadable, but a Lufkin Wood Rule Red End with Slide Rule Extension, Model No. X48, is still on the market. The next folding rule is this Lufkin Model 1206 aluminum rule with brass hinges. Offerings for sale of examples of this rule on the Internet attribute it to the period from the 1920s through the 1950s. This ruler is 7 inches long folded, and 72 inches long fully extended. The third zig-zag ruler in the Tison Tool Barn is this 24-inch long steel ruler. The only marking on it is the legend "MADE IN GERMANY." It has a leatherette case. The final ruler from the Tison Tool Barn covered in this post is not really a folding ruler, but it is closely related, and is used like a zig-zag ruler. It is an Interlox Master Slide Rule, Model No. 106. Instead of legs swinging on hinges, each segment slides over the next segment, with clips on the edges keeping the segments rigidly in line. (The hinges on zig-zag rulers may loosen with use, allowing unwanted bends in an extended ruler.) It was advertised as ideal for measuring inside dimensions. This example of the Interlox ruler is 72 inches long fully extended. Rulers could be ordered from the manufacturer in one-foot increments of length. This ruler was advertised in a 1915 edition of Popular Mechanics magazine, and remained in production at least until World War II. There are a number of plain old rulers and yardsticks in the Tison Tool Barn, but I'll get around to them some other time.

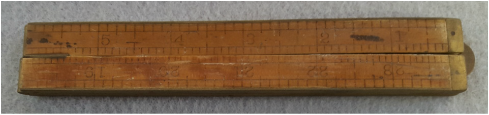

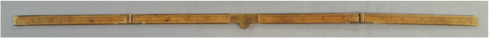

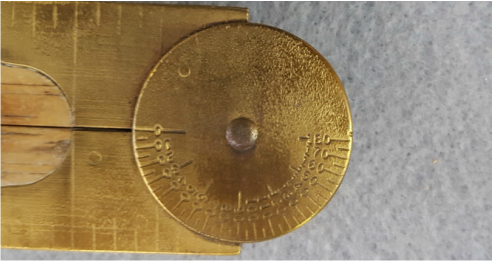

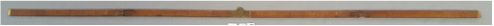

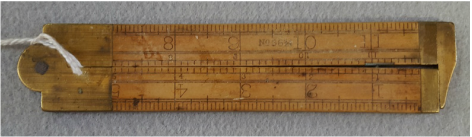

The Tison Tool Barn houses several two-foot long (and one three-foot long) folding rulers. All of those rulers are four-fold. Unlike the one-foot folding rulers described in the previous post, none of the two-foot folding rulers have calipers. Some of the rulers described in this post do have other tools combined with them. Six of the two-foot folding rulers in the Tison Tool Barn were made by the Stanley Rule and Level Company. The collection includes two examples of the Stanley Model No. 62 folding ruler. This model is distinguished by brass banding that covers the narrow sides of the legs of the ruler, and the large brass caps flanking the center hinge. The Tison Tool Barn holds three examples of the Stanley Model No. 68 folding ruler. This model has brass hinges and end caps, but does not have brass edging or any brass flanking the central hinge. The Tison Tool Barn also holds a Stanley Model No. 84 folding ruler. The Model No. 84 has brass banding flanking the center hinge, similar to the Model No. 62 shown above, but does not have brass edging on the narrow sides of the legs. The Tison Tool Barn has a few folding rulers made by the Lufkin Rule Co. Two of them are combination tools, and include a spirit-bubble level and a bevel, or angle-gauge (a protractor). The latter allows a worker to measure and transfer angles. First is this Model No. 863 L. Next is the Model No. 873 L. The spirit-bubble on the Model No. 873 L is slightly shorter, and positioned a little closer to the central hinge, than that on the Model No. 863 L. There is also a difference in the profile of the brass banding next to the center hinge. Another Lufkin folding ruler in the Tison Tool Barn is the Model No. 3851. Unlike the other rulers covered in this post, the Model No. 3851 is three feet long when fully opened. It is a four-fold ruler, so each segment is nine inches long, The last item in this post, from the first half of the 19th century, is older than the others covered here. The ruler is marked "J. WATTS BOSTON." Joseph Watts is known to have produced tools in Charleston, Mass. from 1834 until 1849. This ruler is two feet long, and four-fold. One end segment has an extension bar, which may be slid out almost six inches. This feature makes it easy to measure inside an opening of up to almost 2-1/2 feet across, using only one hand to hold the ruler. (Various foldings of the ruler give a base measurement of 6, 12, 18 or 24 inches.) One of the uses for this tool in the 19th century would have been finding the inside diameter of a cask, needed to calculate the capacity of the cask. In my next post I will look at a few zig-zag rulers, and one interlocking or slide ruler, that are in the Tison Tool Barn.

A folding ruler, also known as a carpenter's ruler or mason's ruler, folds or otherwise collapses, so that it is generally between six and eight inches long when folded, and can be kept in a pocket. Carpenter's overalls typically have a special pocket on the side of a leg to hold one of these rulers. (Carpenter's overalls sold today may advertise this pocket as also suitable for holding a cell phone.) Folding rulers have been largely replaced by tape measures, but 'zig-zag' rulers are still being manufactured. Folding rulers have a long history. A (Roman) foot-long folding ruler made of brass was found in the ruins of Pompeii. Folding rulers are known from Italy by the end of the 16th century. Most folding rulers were made from wood, particularly boxwood. Some were made of ivory or bone, while many are now made of metal or man-made materials. Hinges, swivel joints, and bandings were usually made of brass or 'German silver' (a copper and nickle alloy). The Tison Tool Tool barn collection includes about 20 folding rulers. The five rulers covered in this post are all made of boxwood and brass, and all include a caliper for measuring the outside diameter or width on an object. The first three are two-fold, and are one foot long when opened. The caliper on these three rulers each have a bar just over five inches long, which would allow measurement of objects up to about four inches in diameter. First is this folding ruler, a model No. 36-1/2 made by the Stanley Tool and Level Company. This next folding ruler doe not have a manufacturer's mark on it, but it is labeled as a model No. 36-1/2, and was probably made by Stanley. This next folding ruler is also a one-foot two-fold ruler, a Stanley model 36-1/2 R. (Stanley also made a model 36-1/2 L folding ruler, but the Tison Tool Barn does not have an example of that model.) I am not aware of how this ruler (model 36-1/2 R) differs from the plain model 36-1/2. The next folding ruler in the Tison Tool Barn is a Lufkin model No. 386, made of boxwood and brass. It is also one foot long when opened, but is four-fold, meaning that is is only about 3-1/4 inches long when folded. This ruler also has a caliper, but the bar is only three inches long. The last item in this post is not a folding ruler, but at just four inches long, does count as a pocket ruler. It is a Stanley model No. 136 R, and includes a caliper. In my next post I will look at some two-foot long folding rulers from the Tison Tool Barn collection. Sources:

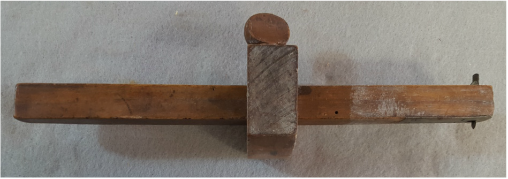

In this post I will describe more marking gauges and related tools from the Tison Tool Barn collection. First is this combination marking gauge. One side of the bar has a single scratch pin for use as a standard marking gauge.. The opposite side of the bar has two scratch pins for use as a mortice marking gauge. The movable scratch pin is adjusted by turning the thumb screw on the end of the bar. One side of the bar of the this gauge has what I thought was a name stamped into it. After applying chalk and carefully examining the mark, I realized that it was a series of depressions in the wood formed by the thumb screw used to hold the fence in place. It therefore appears that at some point the fence was removed from the bar and reinstalled "upside down." The Tison Tool Barn collection includes a couple of slitting cutters. These tools allowed a woodworker to cut strips of thin wood of uniform width. They look like marking gauges, but have a knife blade instead of a scratch pin. The worker would butt the fence up to the edge of the board and draw the cutter along the board. This action could be repeated as necessary until the board was cut through. First is this slitting cutter which is 15-1/4 inches long and can cut a strip up to 10-1/2 inches wide. The wide handle on end with the knife blade helped the woodworker to apply pressure to the knife tip as it passed along the wood. The second slitting cutter in the Tison Tool Barn looks like a simple marking gauge, but it has a knife blade instead of a scratch pin. It is 10 inches long, and can cut a strip up to 9 inches wide. The last tool from the Tison Tool Barn covered in this post is a clapboard siding marker. This tool is used to scribe a line across a clapboard to mark where the board is to be cut. The toothed blade seen in the photo below is adjustable and can be set to the depth desired for the scratch mark. The clapboard is butted up against the end of another board already mounted to the structure, and laid flat on the the vertical edge board at the corner of the structure. The gauge is held over the board so that the projections at the end are against the edge board, and is then moved up and down to scratch a line on the board. Cutting the board on the the scratch line creates a tight fit for the clapboard. This is a Stanley Model 88 clapboard marking gauge. It was patented in 1886, and manufactured by Stanley for more than 75 years. Shown below is the manufacturer's mark on this tool. As often happens, the stamp on the tool is imperfect. In particular, the 'P' in 'PAT.' is missing, and the year looks like '83'. Careful inspection at high magnification shows no sign that the 'P' was ever present, while the last number of the year can be seen to be a '6' with the left half of the number missing. I have used up my buffer of posts for this blog, so I am not sure now what the next post will be about. I am heading back to the Tison Tool Barn to take more photos, and then search the web so I can find something to say about the tools. Sources:

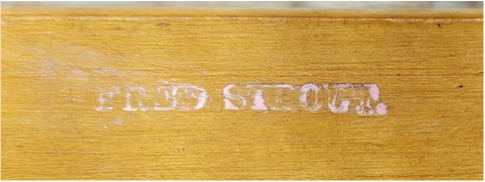

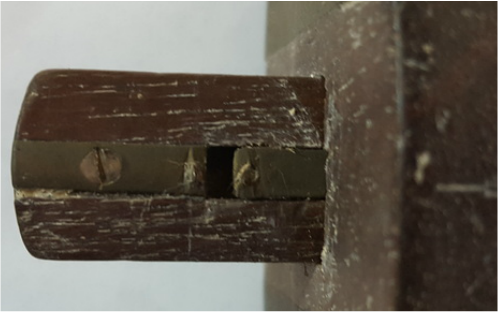

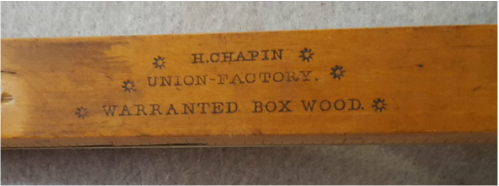

A further note about monkey wrenches: Last week I was made aware of a blog entry on the etymology of "monkey wrench" which appeared after I started my series of blog entries on monkey wrenches in the Tison Tool Barn on September 2, 2015. "Charles Monk, Monkey Wrenches and a 'Monkey on a Stick' - a Gripping History and Etymology of 'Monkey Wrench'". And now a look at marking gauges in the Tison Tool Barn. A marking gauge is a device for marking a cutting line on wood or other materials. The gauge consists of a beam and a fence, through which the beam passes. The fence may be fixed to the beam by a set screw or a wedge. The beam has a scratch pin or other marker set near one end of the beam. The fence is set so that the distance from the inner surface of the fence to the scratch pin equals the desired width of the board or panel. The fence is held against the edge of the wood, and the marking gauge is pushed along the wood, leaving a scratch mark to guide the cut. The Tison Tool Barn has two standard or single-pin marking gauges in its collection. Both are recent acquisitions. First is this marking gauge that was donated by Robert Sherman last February. It has an inch-scale printed on the beam. "FRED STROUT.", which is likely an owner's mark, is stamped on one side. Another single-pin marking gauge was in a tool box donated to the Matheson History Museum in October of this year. It is probably beech and has an inch-scale printed on the beam. It is marked "STANLEY NO. 61 MADE IN U.S.A." A mortise gauge is a marking gauge with a short beam and two scratch pins. One of the scratch pins on a mortise gauge can be moved, making the distance between the pins adjustable. A mortise gauge is used for marking mortises, rectangular holes in wood, into which matching tenons are inserted. Mortise and tenon joints are used in furniture and cabinets, and were formerly used in post and beam construction. The Tison Tool Barn collection includes several mortise gauges. This 6 inch long mortise gauge is made from rosewood and brass. It has a fixed scratch pin near the end of the beam, and a movable scratch pin between the fixed pin and the fence. The movable scratch pin is adjusted by turning the thumb screw at the far end of the beam. The fence is held in a desired position by the screw on top of the fence. The next mortise gauge has a brass bar, and a fence composed of a dense black material with a brass plate on one face. The gauge is labeled in the museum display as being walnut and brass, but I cannot see any grain in the black material, and I believe it is some man-made material. The movable pin is held in place by a set screw. The name "G. F. OWEN" is stamped on several places on the fence. The mortise gauge below is made from boxwood and brass. The bar is 7 inches long, not including the thumb screw. There is an inch-scale marked on the bar. The movable scratch pi is adjusted by turning the thumb screw on the end of the bar. The bar is marked "* H. CHAPIN * * UNION-FACTORY. * * WARRENTED BOX WOOD. *" H. Chapin manufactured tools in Connecticut from 1828 until 1860, when the firm became H. Chapin & Sons. Another marking gauge in the Tison Tool Barn collection is this Stanley #74 double bar marking gauge. It has two bars, 8-1/4 inches long, that can be adjusted individually. Each bar is held in position in the fence by its own thumb screw. This tool can be used as a standard marking gauge by using one of the bars. A mortise can be marked by setting one bar to the distance for one edge of the mortise, and the other bar to the other edge. This requires two passes with the marking gauge, flipping it over between passes. I'll finish describing the marking gauges from the Tison Tool Barn in my next post.

Earlier this year Robert Sherman donated almost 200 items from his collection of antique or vintage items to the Matheson History Museum. The tools from his donation have been added to the Tison Tool Barn collaction. Three of the wrenches that I have highlighted in the previous series of posts were part of that donation. In this post I will feature several items from that donation that were used on farms. YokesThe first item from Mr. Sherman is this shoulder yoke or milkmaid's yoke. It was worn over the shoulders, with buckets of milk or water hung on either side. This yoke appears to have been factory made.  Shoulder yoke from above. Photo by Donald Albury. Shoulder yoke from above. Photo by Donald Albury. Next is another shoulder yoke. This item appears to be home-made. I suspect that the hooks, which are formed from crotches in tree branches, may have been added later to make the yoke appear more rustic. The remaining items in this post were used on animals. There are two yokes for draft animals, almost certainly for oxen. (Horses and mules cannot exert much power on a yoke, and need horse collars for any heavy pulling.) First is a two-ox yoke. The crosspiece of this yoke is smoothly shaped, and probably was produced in a factory or by a craftsman. The oxbows (which curve around the necks of the oxen), however, are branches bent into shape. One oxbow still has its bark, while the bark has been pealed from the other. They are held on the crosspiece by pegs. Next is a one-ox yoke. Oxen were normally used in pairs, but a single ox might be used in specialized tasks, such as turning a cane or sorghum mill. Poor farmers might own only one ox. The crosspiece of this yoke is very rough looking, with minimal shaping of the wood. The oxbow for this yoke is also a branch, but with the bark pealed off. Fence Jumping InhibitorsThe Tison Tool Barn has several items which do not seem to have a common name. These devices, which all appear to be home-made, were reportedly hung around the necks of farm animals to keep them from jumping over fences. I have seen such a device called a "fence jumping inhibitor" in a publication identifying "mystery" farm tools. That name is descriptive, but Google does not return any hits on it. I do not know what farmers may have called them, or even if any two farmers called them the same thing. All photos by Donald Albury. In my next post I will be reviewing some marking gauges from the Tison Tool Barn collection.

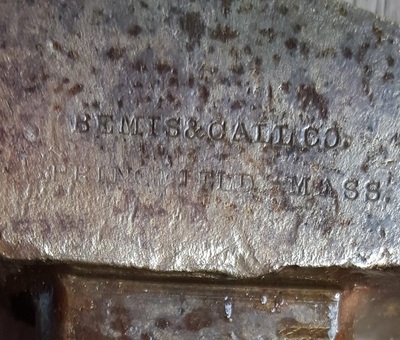

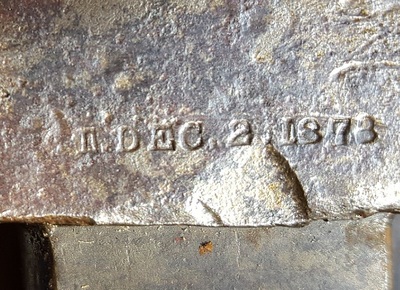

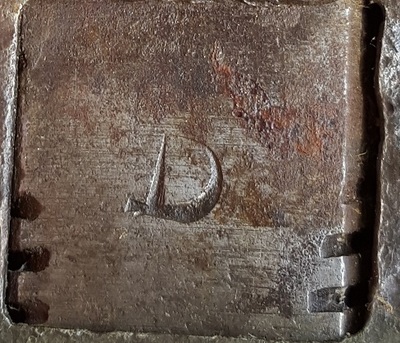

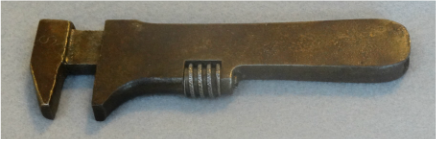

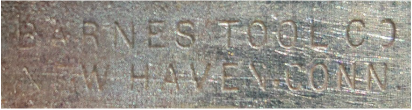

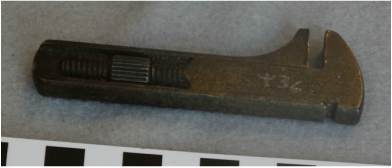

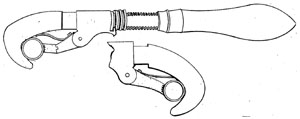

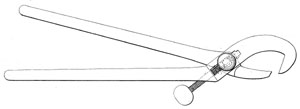

The Tison Tool Barn collection has a few other adjustable wrenches, including three combination wrenches, a couple of pocket or bicycle wrenches, and a couple of other types. A combination wrench is a combination of a monkey wrench and a pipe wrench. The pipe wrench side of a combination wrench works like a screw pipe wrench; it is not "semi-ratcheting" like a Stillson-pattern pipe wrench. The three combination wrenches in the Tison Tool Barn collection are made by the Bemis & Call Hardware & Tool Company. They all have cylindrical wood handles. Models with long and short adjustment nuts were both available. The first combination wrench in the Tison Tool Barn collection is marked "BEMIS & CALL CO. SPRINGFIELD, MASS." on one side of the upper jaw. The number "2" is stamped on the bar below it. "PAT. DEC. 2, 1873" is stamped on the other side of the upper bar. United States Patent #145,085 was issued to W. Chaplin Bemis on Dec. 2, 1873 for an improved wrench, marketed as the Bemis & Call Patent Combination Wrench. This wrench is 15-1/2 inches long. Marks on the 15-1/2 inch Bemis & Call combination wrench. Photos by Donald Albury. The next combination wrench is marked "BEMIS & CALL H. & T. Co SPRINGFIELD, MASS. U.S.A." It also has "6", "8" and "9" stamped, apparently at random, on the bar. The absence of a patent claim or date indicates that it was made after the patent had expired in 1900. It is 11-1/2 inches long and has a long adjustment nut.. The third combination wrench is marked "BEMIS & CALL CO. SPRINGFIELD, MASS. U.S.A." on one side and has a B & C Trade Mark logo in a circle on the other side. There is a "D" stamped on the bar, likely an owner's mark. The absence of patent information on this wrench indicates that it was likely made in the 20th century. It is 12-1/2 inches long and has a short adjustment nut. Markings on the 12-1/2 inch combination wrench. Photos by Donald Albury. The Tison Tool Barn collection includes a couple of small wrenches that were known as bicycle or pocket wrenches. First is this 5 inch wrench marked "BARNES TOOL CO NEW HAVEN CONN." on the bar, and "PAT'D 1886 IMP'D 1892" on the moving jaw. The letter "S", which is likely an owner's mark, is stamped on the opposite side of the moving jaw. The Barnes Tool Company was founded in the 1880s and was still in business in 1909. The original patent for the wrench was U.S. patent #339,813, while the improvement(s) to the wrench were covered by patent #476,079. The second bicycle wrench in the Tison Tool Barn is this four inch long wrench from England. It is marked "•GIRDER MINOR• JOSEPH LUCAS LTD. BIRMINGHAM" on one side. The Joseph Lucas and Son logo, consisting of a torch imposed on a wheel, is on the other side. The Lucas Girder wrench was patented in Great Britain in 1897, and continued in production well into the 20th century. Lucas and Son produced wrenches with a wide variety of markings, branded as "Girder", "Girder Minor" and "Girder Major". Most of the Girder wrenches that I have seen pictured on the Internet have a model number, and "England" instead of "Birmingham." This wrench looks like a Girder No. 93, although there is no model designation on the wrench. The Girder wrench also has the letter "S' stamped on it. This is probably an owner's mark. The Tison Tool Barn has several wrenches with the same style and size "S' stamped on them. It is possible that these wrenches had an owner in common, and that the set had not been broken up when John Tison acquired them. Detail photos of markings on the Girder Minor wrench. Photo by Donald Albury. The next wrench is a Ripley's Patent Wrench, also called a pincer-wrench or pliers-wrench. Ezra Ripley received U.S. patent #16,997 for his "Improved Adjustable Pincer-Wrench" on April 7, 1857. This wrench consisted of two parts that could be separated. The bar of one piece fits through an opening in the other piece, and can be slid back and forth until the jaws fit a nut. When the handles are squeezed, serrations on the two pieces lock together, allowing torque to be applied to the nut. The example of this wrench in the Tison Tool Barn differs from the patent drawing in having a screwdriver bit on the end of one handle. The last wrench I am presenting in this post is a crescent wrench. Crescent wrenches were originally wrenches made by the Crescent Tool Company. While the Crescent Tool Company has been a major source of such wrenches for more than a century, "crescent wrench" has become a generic name for a style of wrench produced by many companies. Crescent wrenches have an adjustable set of jaws in which the working faces of the jaws are (more or less) parallel to the line of the wrench's handle, rather than perpendicular to the line of the handle, as in monkey wrenches. Wrenches with such jaws began appearing in the middle of the 19th century. By 1910 the Crescent Tool Company had introduced an adjustable nut wrench, apparently based on one manufactured by the BAHCO company of Sweden, that became known as the crescent wrench. Besides the manufacturer's marks, this wrench has the initials "S. E. S." stamped on it. This brings my tour of the adjustable nut wrenches in the Tison Tool Barn to an end. In my next post I will look at some hand-made farm tools the Tison Tool Barn collection.

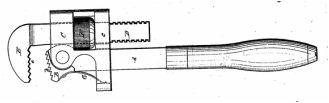

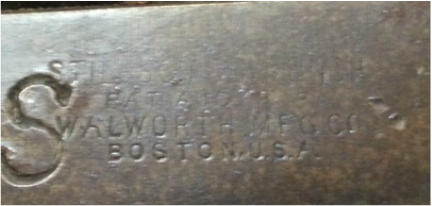

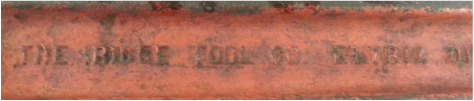

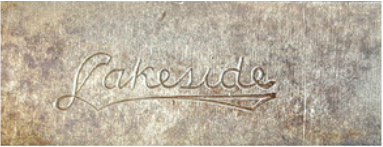

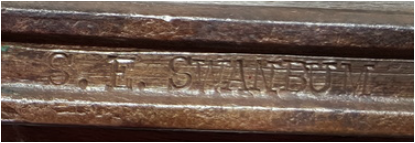

Pipe wrenches are tools used for turning plumbing pipes and other round objects made from soft iron. In the past, water, steam and gas distribution lines were assembled from iron pipes (steam and residential gas lines still use iron pipes). Sections of iron pipe are threaded on both ends and screwed into connectors and other fixtures that have internal threads. Each joint must be leak-proof, which requires that considerable torque be applied in turning the pipes and connectors. Nut wrenches, such as the monkey wrenches I have discussed in the previous posts, cannot get a grip on round objects. Wrenches specifically designed to grip pipes and other round objects began to appear In the middle of the 19th century (a U.S. patent for a "Screw Wrench for Grasping Cylindrical Forms" was issued in 1849). Early pipe wrenches were generally one of two types, screw wrenches, which were fastened to a pipe by tightening an adjustment screw, and tongs, which usually required two hands to pull the handles towards each other while turning the pipe. Screw wrenches could be turned with one hand, but if there was not clearance for the handle to swing in a full circle, the wrench had to be repeatedly loosened and reset to finish turning a pipe. On the other hand, tongs could be easily loosened and reset, but were very awkward to swing through a full circle without loosing their grip on the pipe. In 1869 Daniel Chapman Stillson invented a new type of pipe wrench. One jaw on a Stillson wrench swivels, so that pushing the wrench handle in one direction grips the pipe, while pushing in the other direction releases the pipe. A screw knob adjusts the jaw opening to fit a particular size pipe, but once set, does not need to be changed as long as the wrench is used on that size pipe. The Stillson wrench is "semi-ratcheting." A pipe is turned in one direction as the handle of the wrench is moved back and forth. A Stillson wrench may also be swung in a full circle without losing its grip, as long as pressure is applied continuously to the handle. Daniel Stillson worked for the Walworth Company. When he showed the prototype of his wrench to company executives, they challenged him to test the wrench to see whether it or a pipe would break first. The pipe broke, and Walworth put the Stillson wrench into production. Walworth maintained a monopoly of the production of Stillson wrenches until early in the 20th century, even after the Stillson patent had expired. Walworth was unable to establish "Stillson" as a trademark, and starting around 1905 other companies began producing wrenches that they called "Stillson" or "Stillson pattern". The Tison Tool Barn has six Stillson-pattern pipe wrenches in its collection. First is this Stillson wrench from the Walworth Company. It is 10 inches long, and has a handle made from approximately 20 discs of leather stacked on on a steel rod. The company mark on the wrench consists of four lines, parts of which are badly worn. The first line is "STILLSON'S WRENCH." The third and and fourth lines are "WALWORTH MFG. CO." and "BOSTON, U.S.A.".The second line, however, is particularly hard to read. It starts with "PAT." followed by what appears to be "AUG." Stillson wrenches made by the Walworth Co. after 1882 were marked with a patent date of Aug, 1882. A large letter "S", likely an owner's mark, is stamped several places on the wrench. The wrench is marked as a size 10 (nominal 10 inches). Detail of maker's mark on the Walworth Stillson wrench. A large "S", likely an owner's mark, is also shown. Photo by Donald Albury. Next is a Stillson-pattern wrench made by Peck, Stow, & Wilcox. This wrench has a cylindrical wood handle, which indicates an older model, but it is stamped with the PEXTO logo inside an oval, which indicates manufacture after 1914. "P. S. & W. CO. U.S.A." is stamped in small letters under the logo. It is marked as a size 10. Detail of logo on PEXTO Stillson-pattern wrench. Photo by Donald Albury. Another pipe wrench in the Tison Tool Barn is this 36 inch long wrench made by the Ridge Tool Company of Elyria, Ohio. Its size leaves plenty of room for trade marks and other information. One mark is the patent number, 1,727623, which was issued in 1929, establishing the earliest date this wrench was manufactured. The next pipe wrench has several marks on it, but I have only been able to associate one of them with a manufacturer. There is a mark consisting of an "E" inside a circle, which was used by the Eberhard Manufacturing Company. Some wrenches manufactured by Eberhard were sold under other brand names. The wrench has a mark that looks like a logo, "Lakeside" in script. There was a Lakeside Forge Co. that made wrenches, but this mark does not resemble the logos I have found that were used by that company. There is also a mark, "C. E. SWANBUM", that is probably an owner's mark. As noted in an earlier post, the Tison Tool Barn also has a monkey wrench with the mark "S. SWANBUM," but I do not know if or how the two Swanbums were related, although the two marks look like they were made using the same set of letter punches. Another of the pipe wrenches in the Tison Tool Barn collection has no indication of its origin. The only marks are the number "246" stamped in two places. This wrench has a handle made of more than 35 leather disks and is 16 inches long. Since my last post, the Matheson History Museum has received a donation of a tool box full of tools. I haven't delved very far into the tool box, but a 10-inch Trimo pipe wrench is lying at the top. Trimo was the brand of the Trimont Tool Company of Roxbury, Mass. It apparently was in business from 1902 until 1954. I plan to explore the contents of this tool box in future posts. Addendum: Just hours after I put this post up, I found another pipe wrench in the new tool box. It is a 10-inch pipe wrench from Ridge Tool Co. In my next post I will be be looking at a few other adjustable wrenches from the Tison Tool Barn collection.

|

AuthorI have been a volunteer at the Matheson History Museum. Feeling an affinity with old hand tools (some of which I remember from my youth), I have tried to learn more about the history of the tools in the Tison Tool Barn, and how they were used. All text and photographs by Donald Albury in this blog are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. All illustrations taken from Wikimedia Commons are either in the public domain, or have been released under a Creative Commons license.

Archives

December 2015

Categories

All

Interesting Sites about Old Tools |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed